When filmmaker Derek Smith began sorting through the belongings of his friend Joyce Edwards after she died in 2023, he didn’t expect to uncover more than 100 rolls of unseen film.

Edwards, who died just months before her 100th birthday, had quietly spent the 1970s photographing a squatting community in East London. Nearly 50 years on, her intimate portraits reveal a group of musicians, artists and radicals who reclaimed abandoned houses and, against the odds, built a housing co-operative that still exists today.

Remarkably, Edwards was not a professional photographer. She began taking pictures in her own North London property, capturing a cast of eccentric tenants that included actor Henry Woolf and James Bond villain Vladek Sheybal. But her curiosity soon pulled her further east, towards Bethnal Green, where three streets known as ‘The Triangle’ had been left empty after plans for a major motorway were abandoned.

What she discovered there was a young, makeshift community that had moved into some derelict houses, repairing roofs, fixing plumbing, and turning neglected buildings into liveable homes. Edwards returned repeatedly, earning their trust and creating portraits that feel unguarded, warm, and quietly defiant.

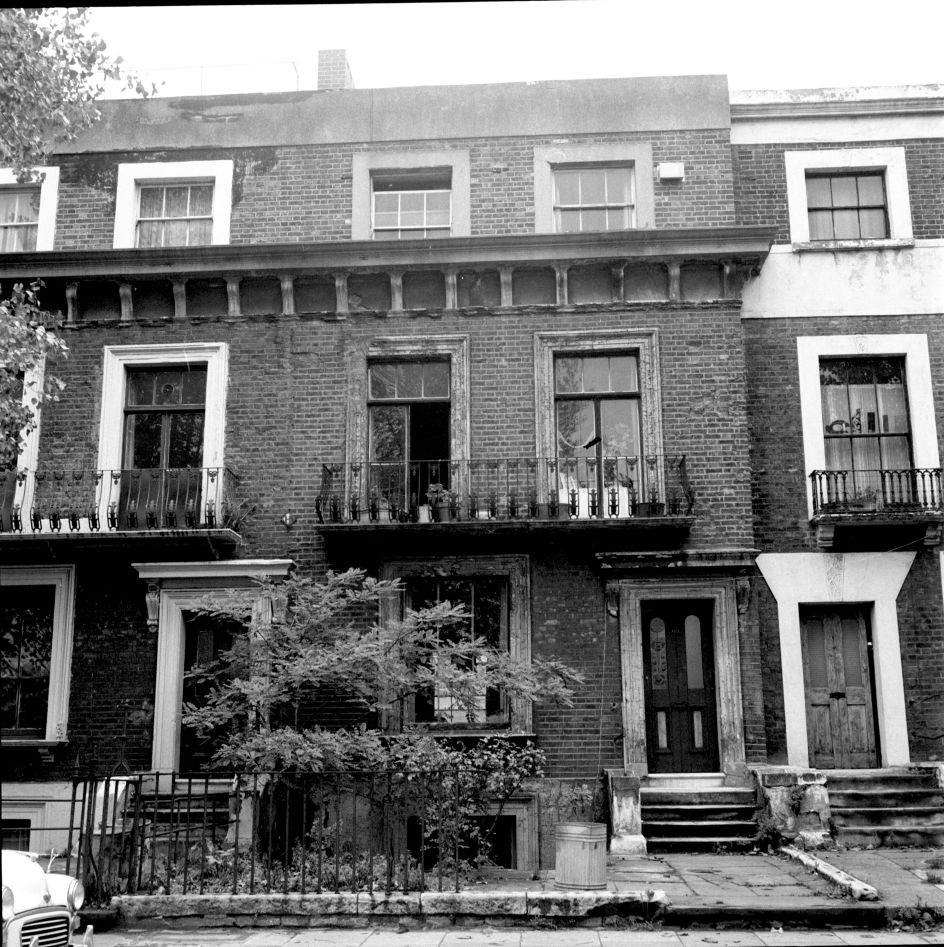

103 Bishops Way 1978, Co-op headquarters © Joyce Edwards

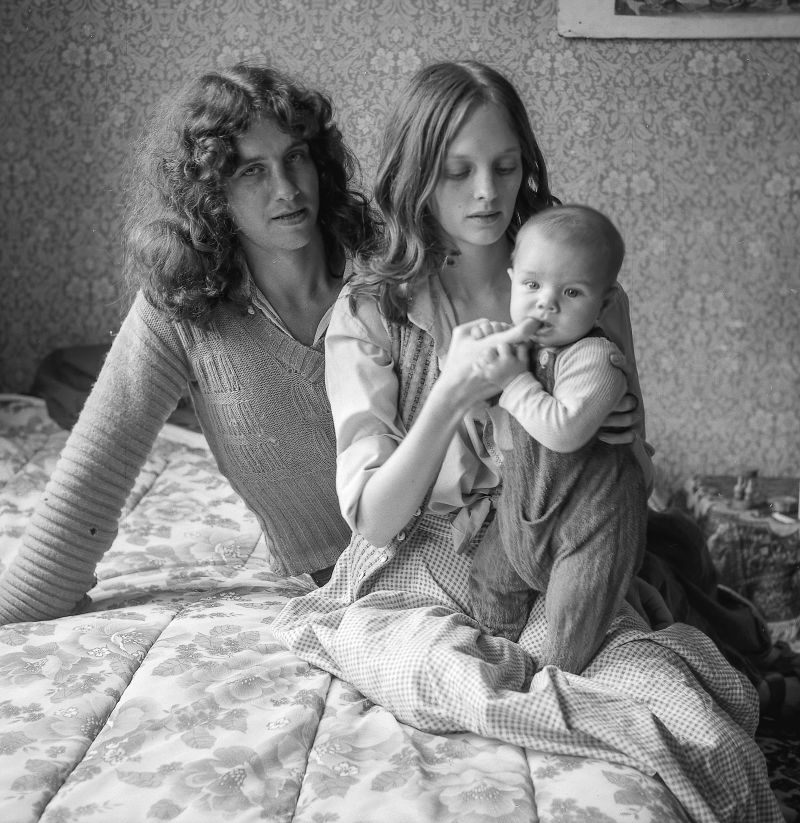

Vanessa Swann and Baz O’Connell, Bishops Way, 1979 © Joyce Edwards

Beverly Spacie, Sewardstone Road, The Triangle, 1977 © Joyce Edwards

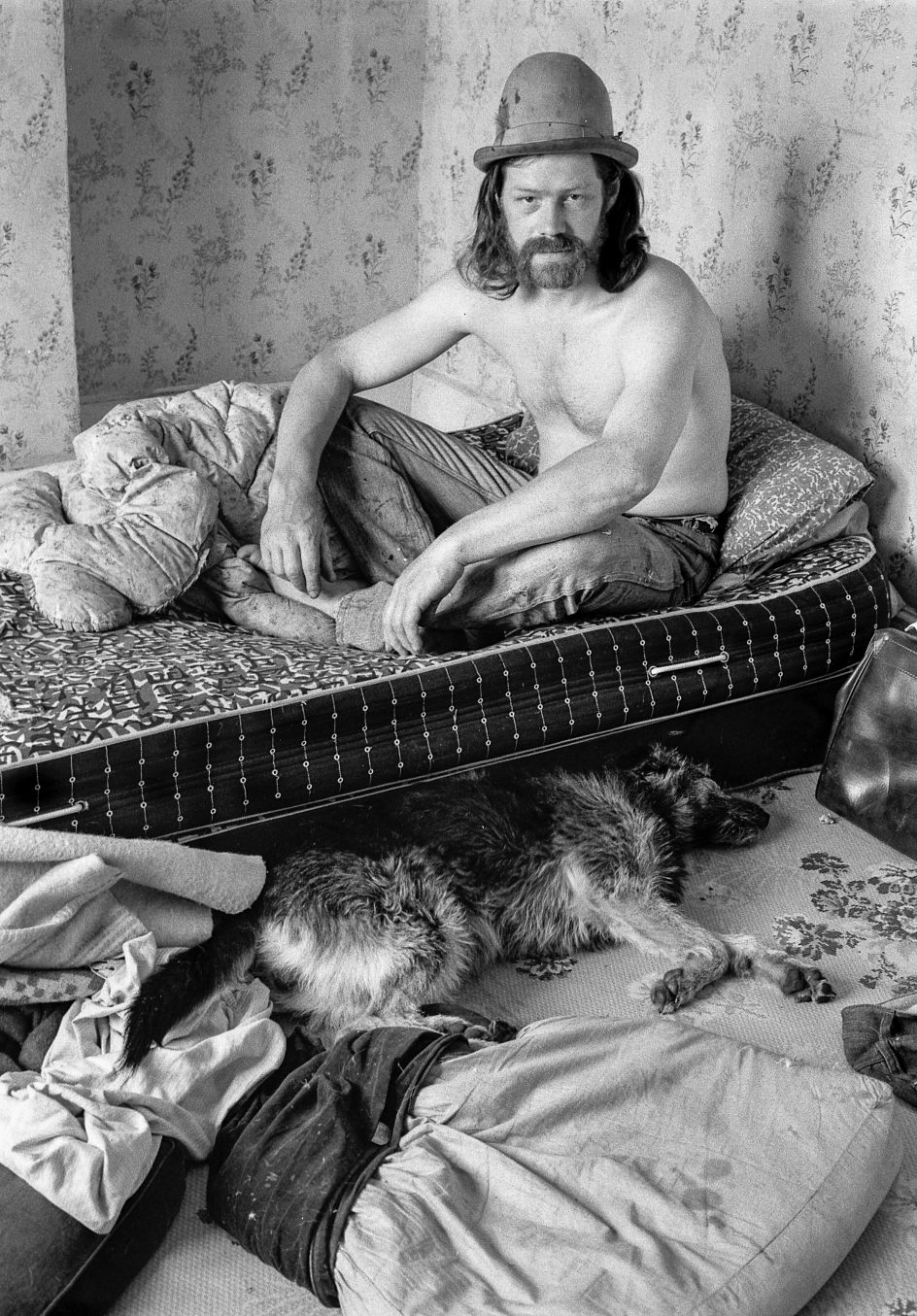

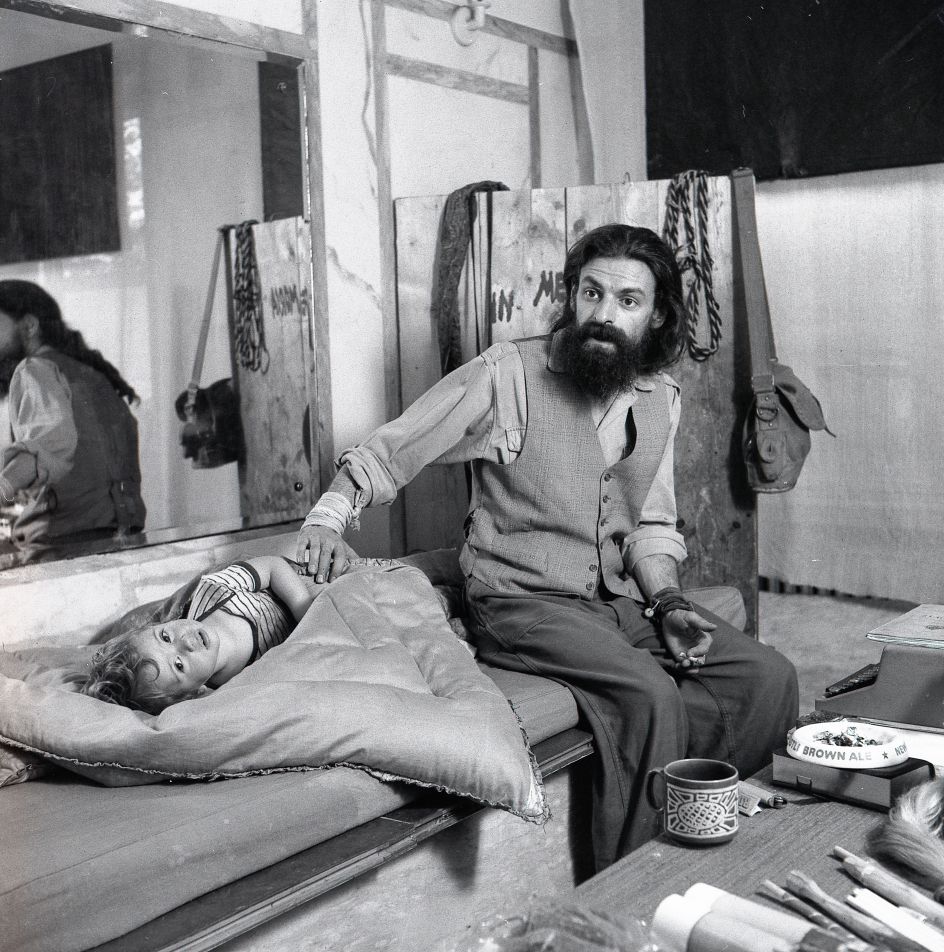

Harold the Kangaroo, painter, with his dog Captain Beefheart, Sewardstone Road 1978 © Joyce Edwards

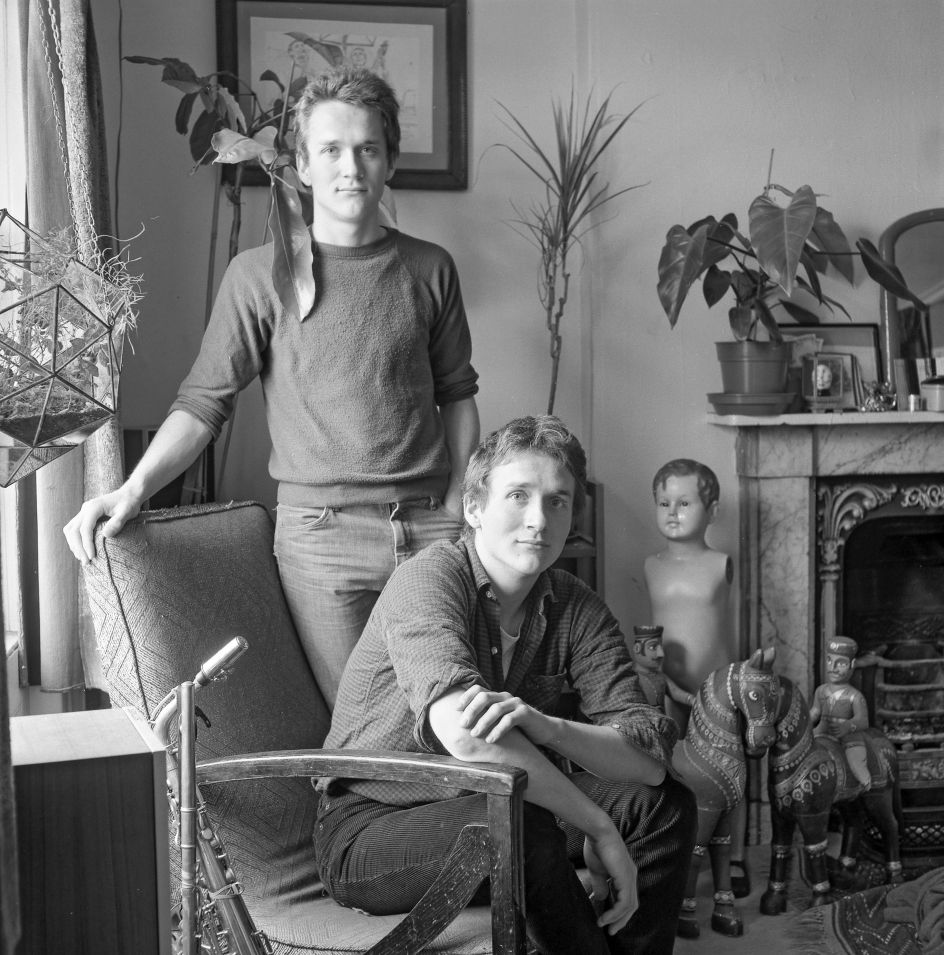

Gary Chamberlin, Beverly Spacie and Howard Dillon, 103 Bishops Way, 1977 © Joyce Edwards

Over two whole years, she built an intimate record of everyday life inside the squats. People cooking, talking, laughing, and resting. Children playing in half-finished rooms. These were not images of protest or spectacle, but of ordinary lives being lived in extraordinary circumstances.

The discovery of Edwards’ fascinating images set off an unexpected chain of events. Derek Smith, who found the rolls of film, was astonished to realise that many of the people pictured were still living in the same streets. Keen to understand how that came to be, he contacted animator and filmmaker Pete Bishop, a co-op member since 1978.

Working with nearby arts charity Four Corners, the group secured National Lottery Heritage Fund support for an oral history project, a film, and an exhibition, bringing Edwards’ photographs back into public view alongside the voices of the people she captured.

Anthony and Andrew Minion, Albany Street squat, 1980 © Joyce Edwards

Tosh Parker, Sewardstone Road, 1977 © Joyce Edwards

Sue, back of Sewardstone Road, 1977 © Joyce Edwards

Father and son at 66 The Bishops Avenue squat, c.1976 © Joyce Edwards

What emerges is a powerful story of resilience and self-determination. The original Triangle squatters went on to form the Grand Union Housing Co-operative, persuading the Greater London Council to allow them to restore their homes and purchase the freeholds of 63 properties in 1981. Today, the community continues to thrive.

As Pete Bishop explains: “The co-op survives because of the involvement of the members, because we are fully mutual and, crucially, because our 1981 constitution includes a no right to buy clause.”

For writer, curator and photographer Gerry Badger, the strength of Edwards’ work lies in its humanity. “When you look at Joyce’s pictures, you want to know about these people. That’s the thing about great portraiture. You want to know what their lives were like and what happened to them. It’s only the really interesting portraits that awaken that kind of impulse in you.”

Shirley Robbins, 103 Bishops Way, 1977 © Joyce Edwards

John, painter, Haverstock Hill squat, 1979 © Joyce Edwards

Joyce Edwards, self-portrait in bedroom, c.1980 © Joyce Edwards