For most of us, the alphabet is something learn early and internalised quickly; a familiar framework we rarely inspect. However, a new book invites us to pause and reconsider this foundation entirely. Alphabetical Playground is an expansive 698-page journey across typographic systems, conceptual alphabets and visual experiments. And its central thesis is that letters are not stable endpoints, but enticing beginnings.

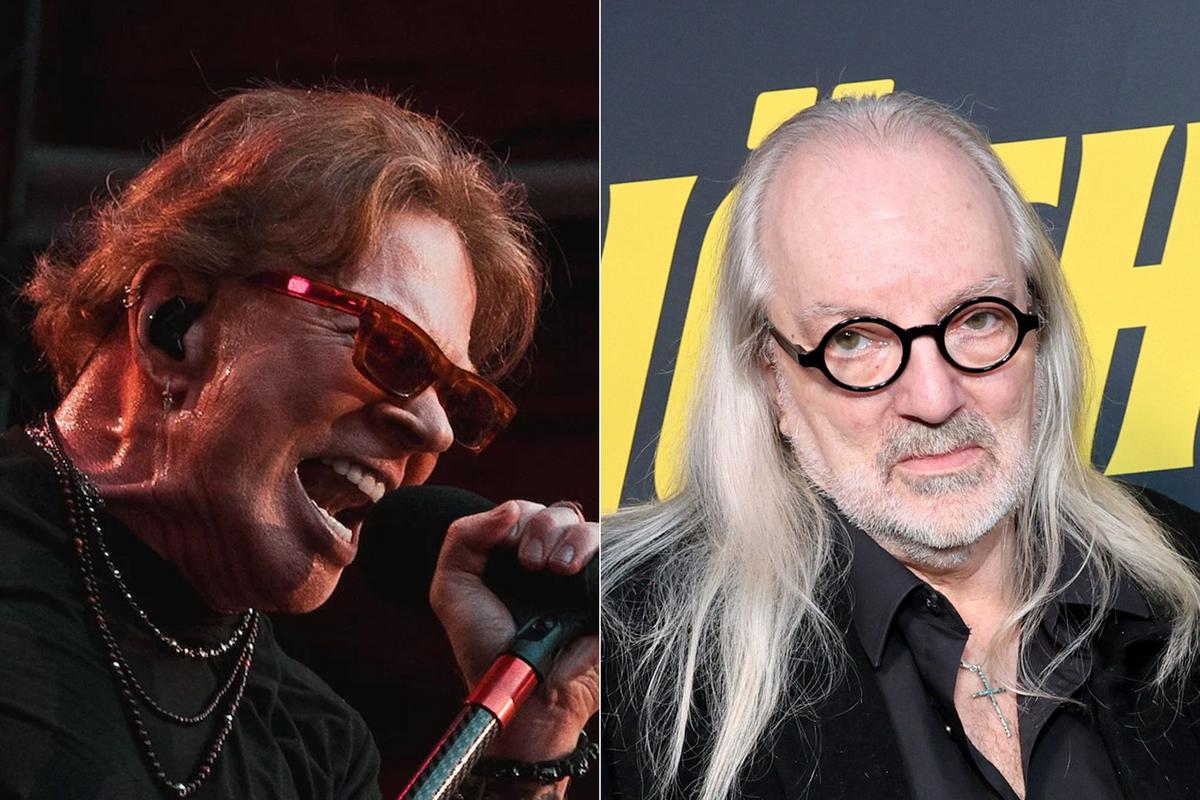

Author Nigel Cottier, design director at Accept & Proceed, is known for leading high-profile commercial projects for brands such as Apple, BMW, Google, Nike, and NASA. Yet alongside this industry-facing work, he’s also spent years exploring how type can be pushed far beyond its traditional communicative function. His first book, Letterform Variations (2021), centred on generating diverse letterforms from a unified system.

Alphabetical Playground, however, is more open-ended and exploratory, spanning 24 themed sections, each gathering multiple alphabets and conceptual research threads.

Alphabet as an open system

So what drew Nigel to see the alphabet as something more than a neutral vehicle for language? “I think it’s the malleability of the alphabet, its capacity to be interpreted in countless different ways,” he replies. “Our alphabet has the scope to be both a communication tool and a container for a variety of conceptual ideas, visual systems and themes.”

This duality is central. The alphabet is familiar enough to be accessible, yet abstract enough to carry other structures, ideas and feelings. Alphabetical Playground is, in this sense, less about showing what letters look like, and more about what they can do. As Nigel puts it: “Typography can be a code within a code, a game within a game, a system within a system.”

In short, the book invites designers to look again at the invisible assumptions underpinning their practice.

Beyond legibility

One of the most striking aspects of Nigel’s work is his willingness to move past legibility. He acknowledges that some alphabets in the book are “almost completely impractical” when judged strictly as communication tools. But this impracticality is the point. As he puts it: “Being able to push type to its limits, and sometimes beyond legibility, is something I find really fascinating.”

This boundary—where letters become something else—is personal and interpretive. “Where is that point where it stops being verbal communication and becomes something else?” he ponders. “Typography can be a beautiful pattern, a puzzle, and a language all at once.”

For designers accustomed to prioritising clarity, this perspective offers both challenge and liberation. It expands what typography can express.

Chaos and control

Despite the book’s visual playfulness, Nigel’s approach is far from arbitrary. He describes his own creative process as being shaped by both structure and surprise. “I love both those words, chaos and control,” he stresses. “The idea that something can embody two seemingly opposing qualities is really alluring.

“I’ve always been interested in using numbers, formulas and patterns to generate visually expressive forms,” he continues. “Creating systems and formulas can sound rigid and ‘unartful’; however, allowing the system to create the form often leads to surprising, even serendipitous outcomes.”

In other words, structure does not eliminate freedom. Instead, constraint can produce unexpected beauty.

Beyond typography

While Nigel acknowledges typographic influences such as Hamish Muir and Paul McNeil, his references span far beyond the field. He’s also drawn to algorithmic and conceptual artists, including Sol LeWitt, Vera Molnár and Manfred Mohr, as well as visual abstractionists such as Bridget Riley and Ellsworth Kelly. “They’re evoking feeling through shape and form,” he explains, noting that meaning does not always require linguistic clarity.

He also speaks warmly of discussing Alphabetical Playground with Hamish Muir, who wrote the foreword. “It’s reassuring to have someone like Hamish say freedom is good, don’t be bogged down by rules,” he says. Finally, we ask Nigel to finish the sentence “The future of type is…” With characteristic simplicity, he responds: “Whatever we want it to be.”

It’s a pithy answer, but also a profound one; a reminder that the alphabet is not finished. It has always been changing, shaped by cultures, materials, tools and technologies.

What Alphabetical Playground underscores is that designers can play an active role in that evolution. For creatives, then, this book is more than a reference. It is a call to look again at the systems we take for granted… and to push them further than ever before.